If you would have asked me 20 years ago whether I believe reality is a simulation, I would have been almost 100% sure it is not. However, today I’m not so sure anymore.

The reason for the change is simple: 20 years ago I would have based my answer on the level of technology available at that time. Now I understand that our current technological level is irrelevant in trying to figure out whether reality is a simulation or not.

We’ve Seen It In the Movies

Many of you’ve probably seen the movie/trilogy called Matrix. The main character, called Neo, learns that his life is not “real” but that he has been living his whole life in a simulated reality, made by a computer. Neo has a physical body and brains but his perception of the world around him is fed into his nervous system via a connector on his neck. Once freed, Neo learns about the real reality and finds out that the year in the real world is way ahead of that in the simulated reality, which he though was the real one.

There are many other examples of simulated reality in fiction (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simulated_reality_in_fiction). The idea is not new. Plato played with the idea in his Allegory of the Cave text as early as 380BC. In a Chinese book Zhuangzi (from the 3rd century BC) is a story called The Butterfly Dream in which a man dreams of being a butterfly. When he wakes up, he is not sure whether he is really a man who dreamt of being a butterfly or a butterfly who now dreams of being a man.

Plato’s Allegory of The Cave, by Jan Saenredam, according to Cornelis van Haarlem, 1604, Albertina, Vienna

Simulations are not only fiction anymore. There is a huge number of computer simulations ran every day for different purposes. We simulate air masses to predict tomorrow’s weather forecast, we simulate transfer and scattering of photons inside human body in radiation therapy, we simulate small virtual worlds in realistic 3D computer games for entertainment and so on. I myself have written several computer programs during the past decades that can be considered to be simulations of some kind of reality. These programs include computer games, physics engines and particle simulations.

The fact that we have created simulations raises our awareness of the possibility of reality being a simulation but it does not, in my mind, provide any added certainty to the probability of reality being a simulation. Is there a way to estimate the probability for us living in a simulated reality? That’s what I try to find out in this blog post.

History As a Facade

Before trying to convince myself that simulated reality might be highly probably, let’s figure out what it would mean to create a simulated reality identical to the one we live in.

To us universe appears to be a pretty complex system. It also appears to contain a lot of “stuff”. Roger Penrose estimated that the number of baryons in the observable universe is about 1080. If we assume a binary based computer system and make a grossly optimistic estimate that we would be able to represent each baryon with a single bit, it would require 1,25 * 1079 bytes, or about 1,137 * 1067 terabytes of storage to store the state of the universe, assuming no compression is used. In 2013 – according to some estimates – there was approximately 4 * 1021 bytes worth of data on the internet. Let’s double that to account for any storage outside the internet. We would then have about 8*1021 bytes available on our computers today. We would therefore need 1250000000 0000000000 0000000000 0000000000 0000000000 000000000 times more computer storage to satisfy the need for storing all baryons for the simulation. I don’t care to estimate the amount of physical space needed to have such an amount of bytes available but you get the idea: according to our standards, that’s a helluva lot of storage space.

However, if you take a solipsistic approach, you don’t need to simulate the entire universe. You only need to simulate the life of one person, namely yourself. Number of baryons observed by a single person is a lot less than the total number of baryons in the universe. You would save a considerable amount of storage space and computing power when you simulate the life of just one person. In addition, you don’t need to run the simulation from the beginning of time, but start instead, say from year 1967. You’ve already saved some 13798000000 – 47 years worth of computation time in the simulation. Even if you include all 7.2 billion humans into the simulation, you would get a saving of similar magnitude in the simulation storage size and computation time.

But wait, can we really skip the odd 13,7 billion years from the simulation and start from the modern times? Aren’t we clever mammals and learn more and more about our own and universe’s history all the time? Surely this information needs to be available in the simulation for us to explore it and learn about times long gone. I cannot say whether the reality simulation would require the total history of the universe as been simulated properly in order for the simulation to be coherent and plausible but I can offer a programmer’s point of view to this dilemma.

I started programming in 1983/1984 and have been programming ever since. During these years I’ve met a lot of talented programmers and seen a lot of code. It is safe to say that I know the mind of a programmer. If I was asked to create a computer simulation that would simulate our reality, I would say “No”. After been offered enough dark chocolate, red wine, marine plywood, epoxy and time to build my own wooden sailboat, I would agree to at least give it a try.

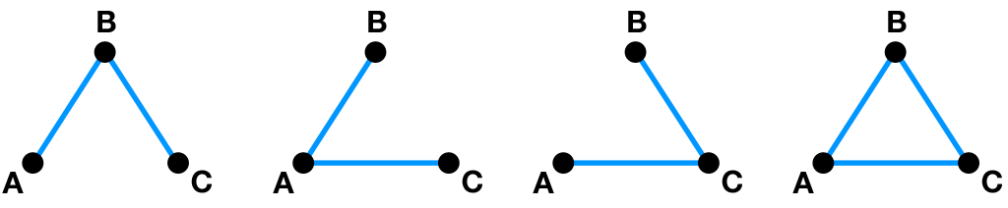

I am, like most programmers, lazy. But in a good way. I want to minimise the amount of code I need to write, with a few exceptions of infamous copy-pasting here and there. I would first try to set up a set of simple rules that would produce the multitude of complexity we seem to experience in our reality. These rules would need to be expressive enough to create things like stars, galaxies, planets, animals, plants and so on. If I would be able to find such a set of rules (which I seriously doubt), I would then run the simulation from the beginning of times until it reaches present time and check that it looks ok. Then I’d let the simulation continue to run on its own and start building the boat.

If I, however, was unable to find such rules or would not have time to run the simulation from the beginning of times, I would probably try to come up with a set of less expressive rules that would be enough to simulate our present time and then make some custom rules to account for the past, starting with more fine detailed rules for the history close to us and then proceeding to coarser and coarser rules for the events in the history further away from our present time. This way I wouldn’t have to run the simulation for the entire history but have a “fake” history governed by the custom rules and hope nobody notices the inevitable mismatches on the boundaries of my custom rules. History would be just a facade, simulated accurately enough to satisfy the curious mind of the clever mammals living inside the simulation at present time. Again, I seriously doubt I could manage to do this approach, either.

If, instead, they told me it is enough that I create some simulation that is interesting and intriguing enough but doesn’t have to be representing our reality, it would be fairly simple to do so. Depending on the complexity, I would choose either the “set of rules to simulate the entire universe” approach or the “history as a facade” approach and be done with it1. Like I mentioned earlier, humans have already created thousands of simulations. They are no way near as complex as our reality appears to be, but they can be considered to be simulations of some realities.

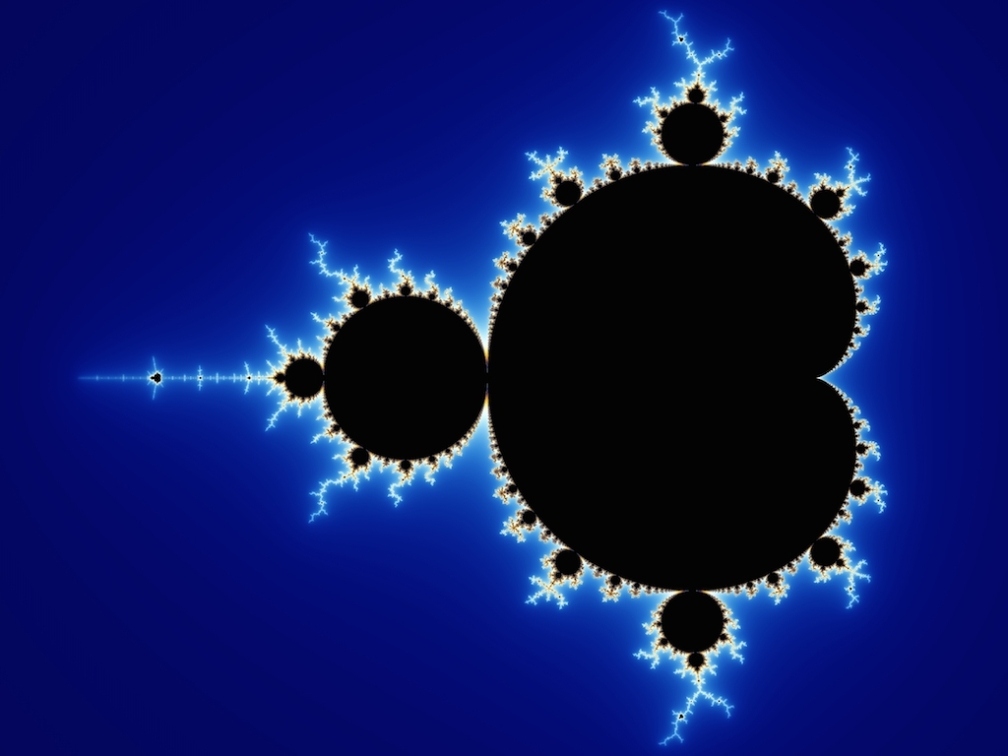

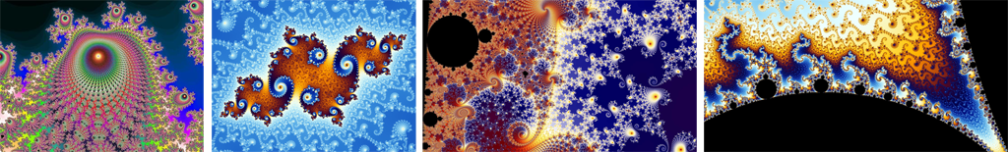

We Can Be in a Very Simple Simulation, Even Though We Think Our World Is Complex

Let’s accept for the moment that, in principle, there is no difference between our reality and the simulations we already run on our computers. Although our reality is far more complex, vast and spans an enormous distance in time, the principle is the same: events happen, things interact with one another and there is a set of rules that govern how things proceed. The only difference is that reality is a bit more advanced simulation 🙂

Now I know some readers are not happy with this comparison. So I need to address some issues and explain why I think our reality can be compared to computer simulations. Depending on the reader, many things might spring to mind that are unique to our reality and do not exist in any simulation done so far. Such things might include consciousness, concept of life, free will, soul and quantum physics, among others.

I won’t be able to go through all of these in detail. The first four are similar and I will handle them as one group. The last one is a bit different but similar to the first group. I’ll try to explain why I don’t consider these to be a problem.

Many will say that there is something special we humans possess. Call it consciousness, free will or soul, it is something that separates us from other animals and makes us special. In addition, many think that these properties can be separate from our physical bodies and cannot ever be explained by laws of physics. I’ll talk about these subjects in my next post but for now I shall simply list the reasons why I think these properties are not anything special:

- This kind of reasoning is so human-centric, it stinks. Looking back at our history, it can be seen that humans have always considered themselves as the centre of attention. Before Copernicus, we thought the earth was the centre of the solar system and other celestial objects revolved around our planet. Thinking that humans possess something other animals do not is a direct continuity in this line of thinking. I believe there is no meaningful distinction between humans and other animals. In fact, I believe there is no distinction between us and other entities in the world, including plants, rocks, matter and so on. There are only different levels of complexity, different levels of grey, so to speak, but we all of the same colour, nonetheless.

- If consciousness, free will or soul would be separate from our physical bodies, how come it’s so easy to alter them with chemicals that interact with the brain? Drink a bottle of whiskey in one continuous sip and I dare you to make any conscious decisions that day 🙂

- There is simply not a single evidence or proof available to support a statement that consciousness or soul can live outside a human body.

I don’t mean these things don’t exist. I simply mean they are an emerging result of yet unknown series of operations inside our brain and are merely labels or definitions we have given for these operations. I’m sure animals, plants and other entities in the universe possess these same qualities, depending only on the amount of liberty we allow for these labels or definitions. So, I’m not against consciousness, free will or soul. I’m simply saying they are not anything a simulation couldn’t reproduce. Concept of life is even a broader definition and purely semantics in my opinion.

About quantum physics. I love Feynman’s QED for its clarity and simplicity but I don’t claim to be an expert on the subject. QED gives us a well-defined way of calculating the probabilities for particle positions according to quantum mechanics but it does not predict where an individual particle will be at a given time. And as far as I have understood it, not only does it not predict individual particles, it is said that it is impossible, because of the uncertainty principle or to put it more profoundly: because nature does not work that way.

If there is something in the quantum phenomena that cannot be predicted or calculated, how could a simulation produce our reality? I don’t know. My intuition tells me quantum uncertainty is not something profound but it is something that can be predicted but we haven’t figured out how to do it yet. I might be wrong, of course. However, if probability distribution is all that is outside that which can be calculated, the simulation could simply include a random generator which serves as the unknown. I’d give it a go.

Finally I get to my point for this section. Think for a moment reality is a simulation. According to our standards, our universe is too complex for us to understand and we cannot see how we could simulate anything that complex. However, our standards are not significant. If our (simulated) reality has been created by a far more advanced entity, our seemingly complex universe would be child’s play for her. There is no reason to assume there cannot be vastly more advanced entities in the “real” reality and they could easily run a simulation such as our universe. One could wonder, why would they bother to run a simulation which is far simpler than their own reality. Wouldn’t they prefer running a simulation which more closely resembles their own reality? Maybe they don’t know how to, just as we don’t know how to simulate our reality. Instead we run thousands of simulations which are far simpler than our reality. Notice the analogy?

So, if you accept the possibility that there can be far more advanced entities in the “real” world, it is reasonable to accept the possibility that they can simulate a universe such as ours.

If You Accept It Could Be Done, Neo Most Likely Is Your Neighbour

So far I have reduced the possibility of living in a simulation to the possibility that they are more advanced entities in the “real” reality2. Since there can be only one “real” reality3 and several simulated realities, the probability that we are in a simulation is greater than the probability for being in a “real” reality. If, for example, 1000 simulations have been created that are at least as advanced than our universe, there’s a 99,9000999001% change we are in a simulation and only 0,0999000999% change we are in a “real” reality.

So the question we should ask is: “how likely it is that there exists a reality far more advanced than ours?” Remember also that our universe might evolve to become such a reality in the far future. If you can imagine us evolving to a state where we would be able to simulate reality as it is in 2014, you need to accept the high possibility that we are inside a simulation already.

Could We Spot Neo?

As far as we are concerned, living in a simulation and not knowing it is identical to living in a real reality. If the creator of the simulation never lets the simulated know of the reality, entities in the simulation have no way of knowing and might as well be convinced theirs is a real one. For some individuals just the thought of simulated reality might be disturbing but majority couldn’t care less, since, for them, there seems to be no evidence to support the argument.

If some speculation is allowed, it might be possible to reveal the underlying simulation. Here’s how:

- First figure out all and complete set of rules that make up the universe. Physicists would call these complete laws of physics the theory of everything. Programmers would call this reverse-engineering the simulation source code. Piece of cake.

- Once the rules are known, we might be able to figure out what kind of “operating system” and “hardware” is used to run the simulation. Another small piece of cake.

- Then all that remains, is to figure out a way to somehow affect the underlying simulation hardware to verify the theory and ensure we are in fact in a simulation. A bit bigger piece of cake, but edible, nonetheless.

If we were able to convince ourselves that we are living in a simulation, this information would be devastating to many of us. Some would not be able to accept the fact that we are merely “bits or numbers” in a program of some sort and do not exist as real human beings. Some might be indifferent, claiming that their life is not affected by the fact. Many people would probably deny all evidence and continue to believe we are real physical beings and claim that the simulation theory is just a hoax.

If there was a way to communicate with our creator(s), things would become interesting. We would be able to learn about the real reality and would most likely get answers to questions that have wondered the human race for ages:

- Why do we exist? Why were we created?

- What’s the purpose of (our) life?

- Who created us?

Getting answers to those questions would be a big deal. It is of course possible and even probable that if we are in a simulation, those who created us are also in a simulation, only in one that is a bit more advanced than ours. Their answers might sound awesome to us, but in reality they would be as “shallow” as our reasons for creating simulations we have already created and are running on computers today. With a communication link to our creators, however, we might be able to convince them into altering the simulation to meet our wishes. That would be a true genie in a bottle -metaphor in practice.

Since there is one real reality, eternal questions still hold and might never be answered to the inhabitants of that reality. Which destiny do you think is better: that we are living in a simulated reality and therefore might be entitled to answers of those eternal questions or that we are living in a real reality and will probably never know why we are here and how we got here?

Epilogue

I just have to say this. There’s about 99.9% chance that any given computer program has a bug. I believe this to be true for advanced simulations, as well. If we are indeed living inside a simulation, shouldn’t we be seeing something that doesn’t seem to work properly or clearly doesn’t make any sense? I’d say commercials in tv, radio and web pages are a strong candidate.

1To be honest, I would be tempted to try a third approach, one which would be cybernetic: code that would alter itself. Just to make things more interesting.

2Not conclusively, but roughly that’s what I have been trying to do.

3One might argue that there can be several “real” realities, as proposed by Everett in his many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. That shouldn’t have an effect on the probability, assuming these worlds are more or less as advanced and capable of running similar simulations.